TamedPUMA: safe and stable imitation learning with geometric fabrics

Supplementary theoretical details on TamedPUMA

A PDF of these supplementary theoretical details can be found HERE.

Energization and Finsler energies

It is common to use a Finsler energy to energize the system, although any Lagrangian can be used. A Finsler energy extends the concept of kinetic energy by enabling the modeling of directionally dependence metric tensors, e.g. the Finsler energy is HD2 in the velocity[2]. Finsler energies have the property that the Hamiltonian $\mathcal{H}_{\mathcal{L}_e}$ associated with the Finsler energy $\mathcal{L}_e$, is the Finsler energy itself. An energized system that conserves a Finsler energy and is path consistent is called a geometric fabric.

To transform the original system $\qddot = \h(\q, \qdot)$ into a geometric fabric, we find $\bar{\alpha}$ for which the system, $\qddot = energize_{\mathcal{H}_{\mathcal{L}_e}}[\h] = \h(\q, \qdot) + \bar{\alpha}\qdot$, conserves the Finsler energy $\mathcal{L}_e$. This energization is performed by setting the time-derivative of the Hamilonian to zero, \begin{align} \dot{\mathcal{H}}_{\mathcal{L}_e} &= \qdot^{\top}[\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\qddot + \vec{\xi}_{\mathcal{L}_e}] = 0,\\ &= \qdot^{\top}[\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}(\h + \bar{\alpha}\qdot)+ \vec{\xi}_{\mathcal{L}_e}] = 0,\\ \bar{\alpha} &= - \frac{\qdot^{\top}\left( \vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e} \h + \vec{\xi}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\right)}{\qdot^{\top}\bf{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\qdot}, \end{align} where $\left(\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\qddot + \vec{\xi}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\right)$ are the Euler-Lagrange equations of $\mathcal{L}_e$ with $\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e} = \partial^2_{\qdot\qdot}\mathcal{L}_e$ and $\vec{\xi}_{\mathcal{L}_e} = \partial_{\qdot \q}\mathcal{L}_e \qdot - \partial_{\q} \mathcal{L}_e$[1].

Theoretical details on the Compatible Potential Method

The stability and convergence properties of the CPM are based on Theorem III.5 in Ratliff et al. (2023)[1]. The Theorem reads as follows, where we correct for two typos, replacing $\mathcal{H}$ with $\mathcal{H}_{\mathcal{L}_e}$ and $\gamma \qdot $ with $\gamma$ in the original description, i.e. \begin{equation} \label{eq: system_CPM} \qddot = energize_{\mathcal{H}_{\mathcal{L}_e}}[\h+\f]+\gamma \qdot \ \ \ \ \text{is replaced by:} \ \ \ \ \qddot = energize_{\mathcal{H}}[\h+\f]+\gamma. \end{equation}

Theorem III.5 adapted from Ratliff et al. (2023)[1]: Let energize$_{\mathcal{L}_e}[\h(\q, \qdot)]$ be a fabric with generator $\h$ and Finsler energy $\mathcal{L}_e$, and let $\f(\q, \qdot)$ be a navigation policy with compatible potential $\psi(\q)$. Denote the total energy by $\mathcal{H}=\mathcal{L}_e+\psi$. The system \begin{align} \label{eq: qddot_theoremIII5} \qddot &= energize_{\mathcal{H}}[\h+\f] - \beta \qdot\\ &= energize_{\mathcal{H}_{\mathcal{L}_e}}[\h+\f]+\gamma %= \h + \f + \bar{\alpha} + \gamma, \end{align} with energy regulator, \begin{equation} \label{eq: gamma} \gamma(\q, \qdot) = - \left(\frac{\qdot \qdot^{\top}}{\qdot^{\top}M_{\mathcal{L}_e}\qdot}\right)\delta \psi - \beta \qdot, \end{equation} converges to the zero set of $\f$ for $\beta>0$.

The proof of Theorem III.5 consists of two parts: (1) Showing that the system in Eq. \eqref{eq: qddot_theoremIII5} is energy-decreasing and therefore it results in $\qdot \rightarrow \vec{0}$ and $\qddot \rightarrow \vec{0}$ as time goes to infinity. (2) Assuring that when the system converges, it converges to the zero set of the navigation policy $\f$.

Step 1: To ensure that the damped system decreases in energy resulting in $\qdot = \vec{0}$ and $\qddot = \vec{0}$, we first analyze the energy-conservative system, $energize_{\mathcal{H}}[\h +\f]$.

Step 1a: Let's start with finding $\alpha$ for which the system $\qddot = energize_{\mathcal{H}}[\h+\f] = \h + \f + \alpha \qdot$ is energy-conservative, i.e. the derivative of the Hamiltonian is zero, $\dot{\mathcal{H}} = 0$. The total energy is a summation of the Hamiltonian associated with the Finsler energy, $\mathcal{H}_{\mathcal{L}_e}$, and the potential energy $\psi$. The total energy and its derivative therefore become, \begin{align} \mathcal{H} = \mathcal{H}_{\mathcal{L}_e} + \psi, && \dot{\mathcal{H}} = \frac{\partial \q}{\partial t}^{\top} \frac{\partial \mathcal{H}}{\partial \q} = \qdot^{\top}[\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\qddot + \vec{\xi}_{\mathcal{L}_e} + \delta \psi]. \end{align} To find $\alpha$ for which $\dot{\mathcal{H}} = 0$, we substitute $\qddot = \h + \f + \alpha \qdot$ into the derivative of the Hamiltonian and set this equal to zero, \begin{align} \dot{\mathcal{H}} &= \qdot^{\top}[\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\qddot + \vec{\xi}_{\mathcal{L}_e} + \delta \psi] = 0, \\ &= \qdot^{\top}[\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e} \left( \h + \f + \alpha \qdot \right) + \vec{\xi}_{\mathcal{L}_e} + \delta \psi] = 0, \\ &= \alpha (\qdot^{\top}\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\qdot) + \qdot^{\top}\left( \vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e} \h + \vec{\xi}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\right) + \qdot^{\top}\left(\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e} \f + \partial \psi \right) = 0.\\ \alpha &= - \left(\frac{\qdot^{\top}}{\qdot^{\top}\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\qdot}\right) [ \vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}(\h +\f) + \vec{\xi}_{\mathcal{L}_e} ] - \left(\frac{\qdot^{\top}}{\qdot^{\top}\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\qdot}\right) \partial \psi. \label{eq: alpha_appendix} \end{align} The expression for $\alpha$ is substituted into the system $\qddot = \h + \f + \alpha \qdot$, to obtain, \begin{align} \label{eq: qddot_conservative} \qddot &= energize_{\mathcal{H}}[\h+\f], \\ &= \h + \f + \alpha \qdot, \\ &= \underbrace{\h + \f \underbrace{- \left(\frac{\qdot \qdot^{\top}}{\qdot^{\top}\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\qdot}\right) [ \vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}(\h +\f) + \vec{\xi}_{\mathcal{L}_e} ]}_{\bar{\alpha}}}_{energize_{\mathcal{H}_{\mathcal{L}_e}}[\h+\f]} \underbrace{- \left(\frac{\qdot \qdot^{\top}}{\qdot^{\top}\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\qdot}\right) \partial \psi}_{\gamma \text{ with } \beta=0}. \label{eq:} \end{align} Analyzing Eq. \eqref{eq: qddot_conservative}, the system can be split into the energized system of $\qddot = \h +\f$ with the Finsler energy $\mathcal{L}_e$ and corresponding energization vector $\bar{\alpha}$, and the term $\gamma$ where $\beta=0$. By adding damping to Eq. \eqref{eq: qddot_conservative}, we obtain the damped system as represented in Eq. \eqref{eq: qddot_theoremIII5}. In Step 1b, it is proven that the damped system decreases energy and converges to $\dot{\mathcal{H}} \rightarrow 0$, since $\mathcal{H}$ is decreasing and lower bounded, leading to $\qdot \rightarrow \vec{0}$ and $\qddot \rightarrow \vec{0}$ as time goes to infinity.

Step 1b: Damping is added to Eq. \eqref{eq: qddot_conservative} via $-\beta \qdot$ with $\beta>0$, \begin{equation} \qddot = \h + \f + \alpha \qdot - \beta \qdot. \end{equation} As the derivative of the Hamiltonian is zero for $\beta=0$, this leads to the following derivative of the Hamiltonian for the damped system, \begin{align} \label{eq: Hdot_damped} \dot{\mathcal{H}} &= \qdot^{\top}[\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\qddot + \vec{\xi}_{\mathcal{L}_e} + \delta \psi] - \beta \qdot^{\top} \vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e} \qdot, \\ &= - \beta \qdot^{\top} \vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e} \qdot. \end{align} As $\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}$ is strictly positive, Eq. \eqref{eq: Hdot_damped} is less than zero for all $\qdot \neq \vec{0}$ and zero for $\qdot = \vec{0}$. Since the total energy $\mathcal{H}$ is always decreasing and lower bounded by zero, the rate of the decrease must converge to zero, $\dot{\mathcal{H}} \rightarrow 0$, which means that $\dot{\mathcal{H}} = -\beta \qdot^{\top}\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\qdot \rightarrow 0$ converges to zero, and therefore $\qdot \rightarrow \vec{0}$ leading to $\qddot \rightarrow \vec{0}$.

Step 2: The second step is to ensure convergence of the system in Eq. \eqref{eq: qddot_theoremIII5} to the zero set of the navigation policy $\f$. For the CPM, this ensures that the system Eq. \eqref{eq: system_CPM} converges to the zero set of the pulled dynamical system of PUMA ($\qddot = \f^{\mathcal{C}}_{\theta}(\q, \qdot)$, Eq. 6 in our paper) which contains the desired goal. To explore convergence of Eq. \eqref{eq: qddot_theoremIII5} over infinite time to the zero set of $\f$, we take the limit with $\qdot, \qddot \rightarrow \vec{0}$, \begin{align} \label{eq: limit_qddot} \qddot &= \h + \f + \alpha \qdot - \beta \qdot,\\ &= \h + \f - \frac{\qdot \qdot^{\top}}{\qdot^{\top}\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\qdot} [ \vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}(\h +\f) + \vec{\xi}_{\mathcal{L}_e} ] - \frac{\qdot \qdot^{\top}}{\qdot^{\top}\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\qdot} \partial \psi - \beta \qdot,\\ &= \h - \frac{\qdot \qdot^{\top}}{\qdot^{\top}\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\qdot}[ \vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\h + \vec{\xi}_{\mathcal{L}_e} ]- \beta \qdot + \f - \frac{\qdot \qdot^{\top}}{\qdot^{\top}\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\qdot} \left(\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e} \f + \partial \psi \right),\label{eq: limit_qddot_c}\\ \xrightarrow[t \rightarrow \infty]{}\ \vec{0} &= \underbrace{energize_{\mathcal{H}_{\mathcal{L}_e}}[\h]- \beta \qdot }_{\xrightarrow[t \rightarrow \infty]{}\ \vec{0}}+ \f - \frac{\qdot \qdot^{\top}}{\qdot^{\top}\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\qdot} \left(\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e} \f + \partial \psi \right),\label{eq: limit_qddot_d}\\ \xrightarrow[t \rightarrow \infty]{}\ \vec{0} &= \f - \frac{\qdot \qdot^{\top}}{\qdot^{\top}\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\qdot} \left(\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e} \f + \partial \psi \right). \label{eq: limit_qddot_e} \end{align} In the limit, both $\beta\qdot \rightarrow \vec{0}$ and $energize_{\mathcal{H}_{\mathcal{L}_e}}[\h]$ converge to zero in Eq. \eqref{eq: limit_qddot_d}. In the following, we will elaborate why the equality in Eq. \eqref{eq: limit_qddot_e} requires $\f=\vec{0}$ in the limit.

The fraction $\frac{\qdot \qdot^{\top}}{\qdot^{\top}\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\qdot}$ in Eq. \eqref{eq: limit_qddot_e} has two occurances of $\qdot$ both in the numerator and denominator. As $\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}$ is positive definite and bounded, the fraction in the limit becomes, \begin{equation} \label{eq: A_limit} \lim_{t \rightarrow \infty}\ \frac{\qdot \qdot^{\top}}{\qdot^{\top}\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\qdot} = \vec{A} = \frac{\vec{v}\vec{v}^{\top}}{\vec{v}^{\top}\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\vec{v}} \ \ \ \ \text{where} \ \ \ \ \vec{v} = \lim_{t \rightarrow \infty} \frac{\qdot}{\norm{\qdot}}. \end{equation} Using the definition for $\vec{A}$ in Eq. \eqref{eq: A_limit}, Eq. \eqref{eq: limit_qddot_e} can be rewritten as, \begin{equation} \label{eq: limit_lambdas} \xrightarrow[t \rightarrow \infty]{}\ \vec{0} = \underbrace{[\vec{I} - \vec{A} \vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}] \f}_{\lambda_1} + \underbrace{\vec{A}(\delta \psi)}_{\lambda_2}, \end{equation} In the limit, the term $[\vec{I} - \vec{A} \vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}]$ has nullspace $\vec{v}$ as $[\vec{I} - \vec{A} \vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}]\vec{v} = \vec{0}$, \begin{equation} \label{eq: spanv} [\vec{I} - \vec{A} \vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}] \vec{v} = \vec{v} - \frac{\vec{v} \vec{v}^{\top}}{\vec{v}^{\top}\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\vec{v}} \vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\vec{v} = \vec{v} - \vec{v} \frac{\vec{v} \vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\vec{v}^{\top}}{\vec{v}^{\top}\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\vec{v}} = \vec{v} - \vec{v} = \vec{0}, \end{equation} which implies that $\lambda_1$ and $\lambda_2$ in Eq. \eqref{eq: limit_lambdas}, are orthogonal, $\lambda_1 \perp \lambda_2$. Both terms must be zero, $\lambda_1 = \vec{0}, \ \lambda_2 = \vec{0}$ for Eq. \eqref{eq: limit_lambdas} to hold. By contradiction, it is proven that $\f$ is equal to zero as time goes to infinity.

Proof by contradiction: Let us assume that $\f \neq \vec{0}$. First, note that if $\f \neq \vec{0}$, for $\lambda_1$ to be zero, $\f$ must be in the nullspace of $[\vec{I} - \vec{A} \vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}]$, which we have already noted is equal to $\vec{v}$. As a consequence, $\f \in \text{span}(\vec{v})$. In contrast, for $\lambda_2$ to be equal to zero, i.e., $\vec{A}(\partial \psi) = \vec{0}$, two cases exist:

- Case 1: The gradient of the potential is equal to zero, $\partial \psi = \vec{0}$. For $\f \neq \vec{0}$, this case cannot hold, as the potential is a compatible potential of $\f$, which indicates that $\partial \psi = \vec{0}$ if only if $\f = 0$, which would lead to a contradiction.

- Case 2: The other possibility is that $\partial \psi$ is in the nullspace of $\vec{A}$, which implies that $\partial \psi \perp \vec{v}$. Consequently, since $\f \in \text{span}(\vec{v})$, $\partial \psi \perp \vec{v}$ implies that $\partial \psi \perp \f$; hence, $\partial \psi^{\top}\f=0$. However, a compatible potential also has the property $-\partial \psi^{\top} \f>\vec{0}$ wherever $\f \neq \vec{0}$, which once again leads to a contradiciton.

Discussion

The metric $\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}$ is additionally assumed to not vanish in the limit $\qdot \rightarrow \vec{0}$. In practice, numerical instability of the fraction $\frac{\qdot \qdot^{\top}}{\qdot^{\top}\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\qdot}$ is avoided by replacing the denominator by $\qdot^{\top}\vec{M}_{\mathcal{L}_e}\qdot + \epsilon$ with $\epsilon>0$.

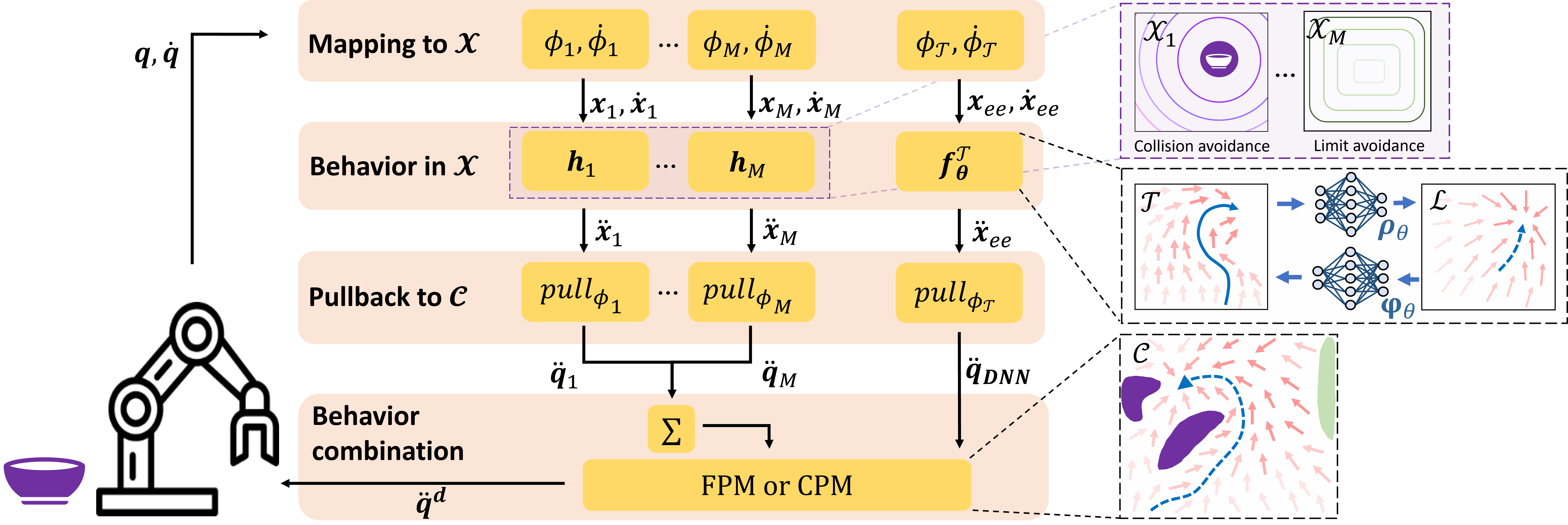

Illustration of TamedPUMA

References

- Ratliff, Nathan, and Van Wyk, Karl. (2023). "Fabrics: A Foundationally Stable Medium for Encoding Prior Experience." arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.07368.

- Ratliff, Nathan D., Van Wyk, Karl, Xie, Mandy, Li, Anqi, and Rana, Muhammad Asif. (2020). "Optimization fabrics." arXiv preprint arXiv:2008.02399.

Related Publications

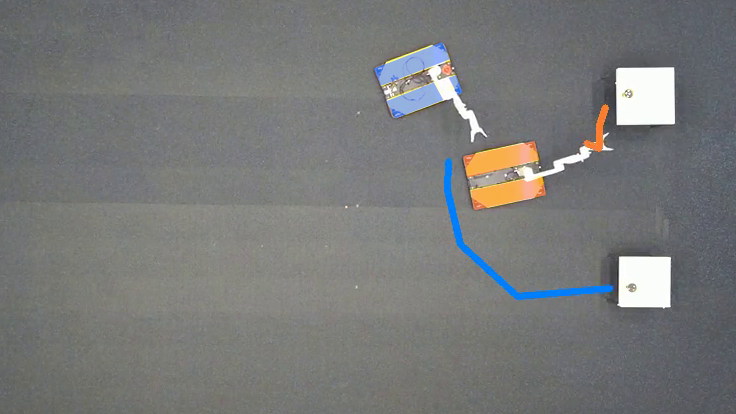

Pushing Through Clutter With Movability Awareness of Blocking Obstacles

In IEEE Int. Conf. on Robotics and Automation (ICRA),

2025.

Globally-Guided Geometric Fabrics for Reactive Mobile Manipulation in Dynamic Environments

In IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters (RA-L),

2025.

Safe and stable motion primitives via imitation learning and geometric fabrics

In Robotics: Science and Systems, Workshop on Structural Priors as Inductive Biases for Learning Robot Dynamics,

2024.

Reactive grasp and motion planning for adaptive mobile manipulation among obstacles

In Robotics: Science and Systems, Workshop on Frontiers of Optimization for Robotics,

2024.

Multi-Robot Local Motion Planning Using Dynamic Optimization Fabrics

In Proc. IEEE International Symposium on Multi-Robot and Multi-Agent Systems,

2023.

Group-based Distributed Auction Algorithms for Multi-Robot Task Assignment

In IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering (T-ASE),

2023.

Integrated Task Assignment and Path Planning for Capacitated Multi-Agent Pickup and Delivery

In , IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters (RA-L),

2021.

Anticipatory Vehicle Routing for Same-Day Pick-up and Delivery using Historical Data Clustering

In Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC),

2020.